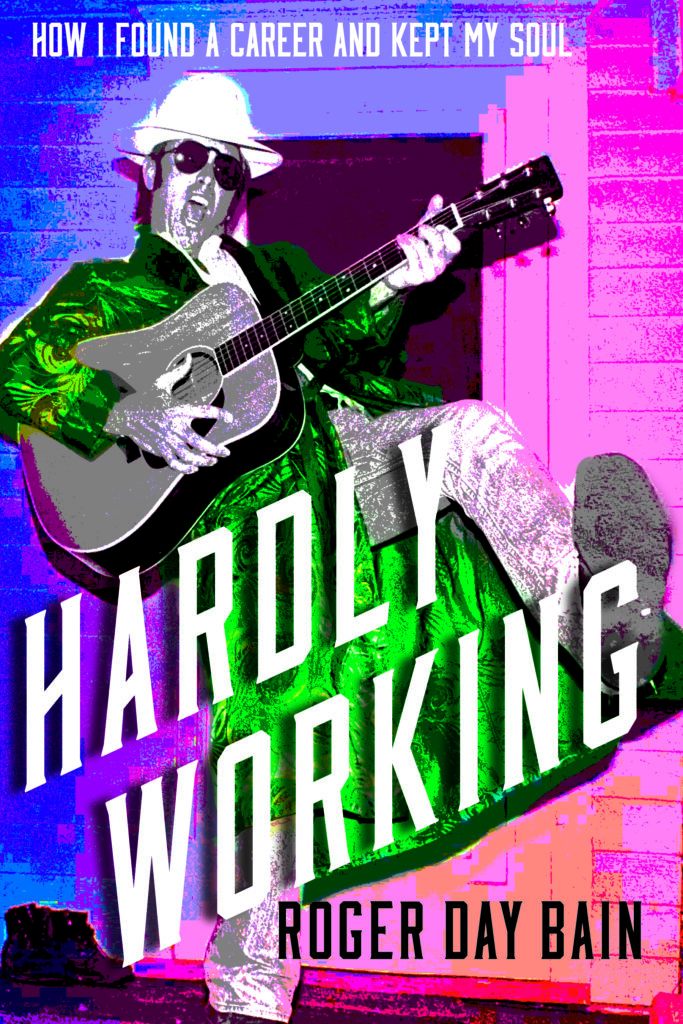

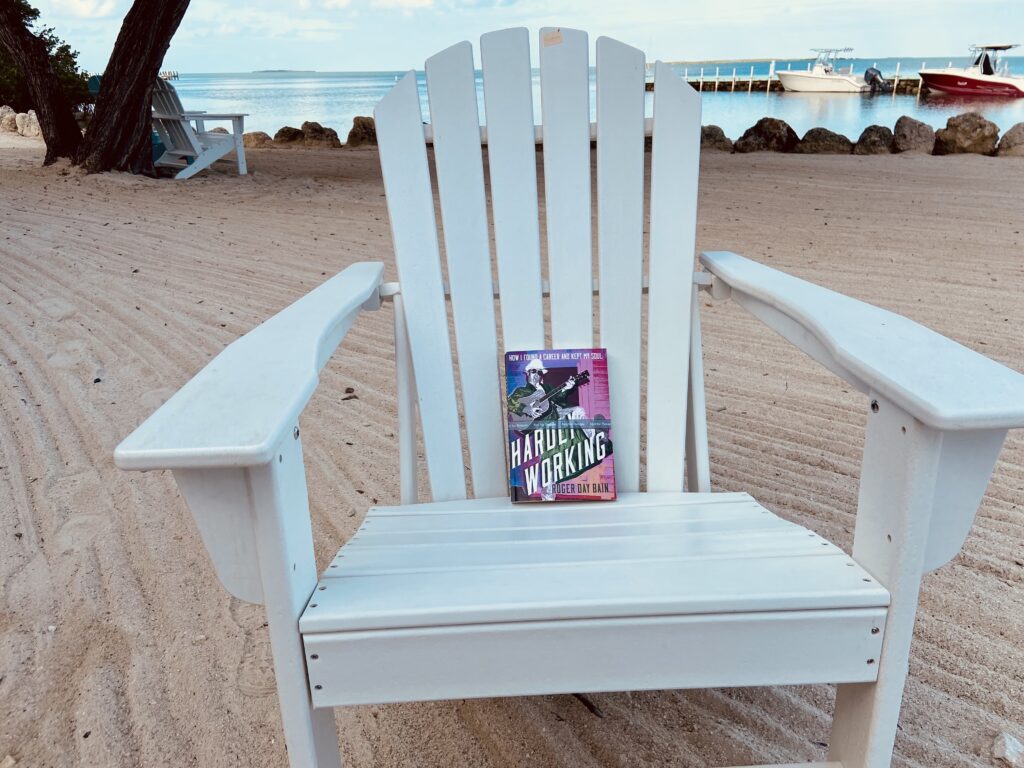

This is the saga of trying to market your self-published book while in a tropical paradise.

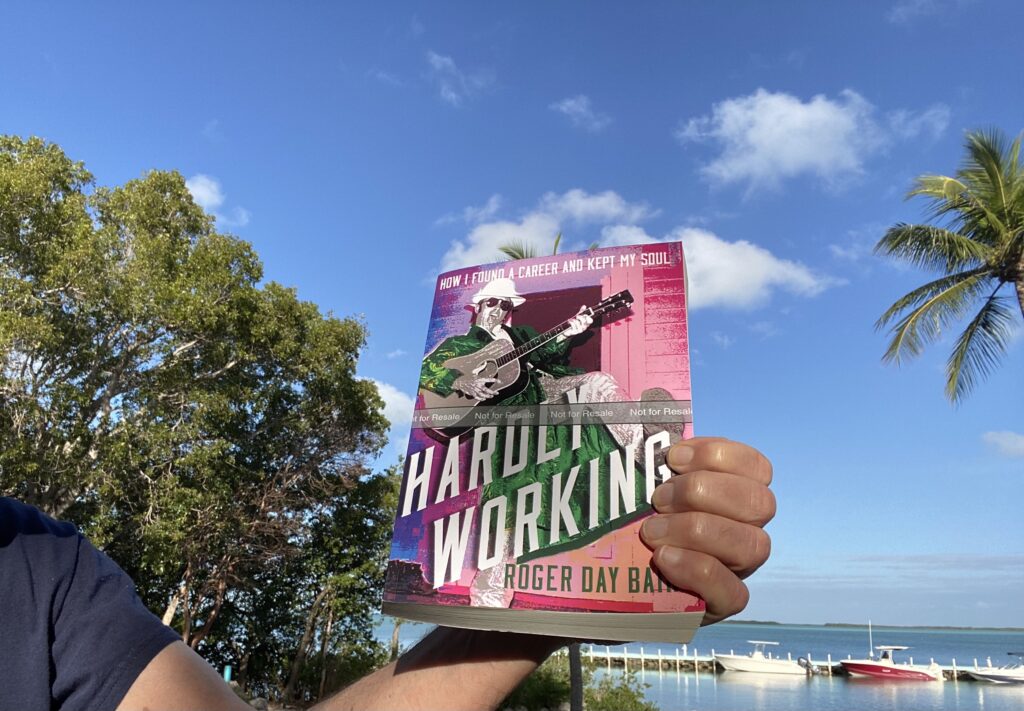

Rock Harbor does not provide a good environment for launching a book. The beach awaits. The Bay awaits. The breeze stands in line, awaiting. There are manatees to spot and Osprey to witness and books to read in the shade of a Mangrove tree. At first, we thought it was a Buttonwood but someone who seemed to know what they were talking about said it’s a variety of mangrove.

A few weeks into the launch, I must think of ways to get someone to write about the book or review it. But who wants to think of these things while on a tropical respite?

There is yellowtail snapper to eat. There are gin and tonics to be made. There is tax preparation to be put off. There is tomorrow, with highs in the lower 80s and a WSW wind at 8. There goes a dolphin. Bring down the paddles.

There is a roof rehab project involving a dozen Guatemalans. Some mornings it sounds like a huge bank vault is being repeatedly dropped over our heads. Will the ceiling crack? There are asbestos particles wafting about. Three old roofs dating back 50 years are being torn off. The workers recline on the asphalt parking lot in the shade after lunch, taking a siesta and thinking thoughts that I can’t imagine. I suppose I could imagine them, but not for the purposes of this extended message.

There is Wordle to play and the Florida Keys Press to hunt down on Wednesdays to see what deals Publix has beginning the next day.

There is sunset to watch. Nearly every night. There is the green flash to look for as the orb sinks into oblivion. There are the people gathered for sunset, one of whom usually has a green flash story. And there is the green flash explanation that has something to do with light rays and water and bounce rate and hydro physics.

There is the crocodile and there are those who have spotted the crocodile and those who have heard of their croc spottings.

There is the downpour on the way home from the Italian Food Company and the rain going right through the tarp over the tables at Ballyhoos, where you have sought refuge, drenching you good.

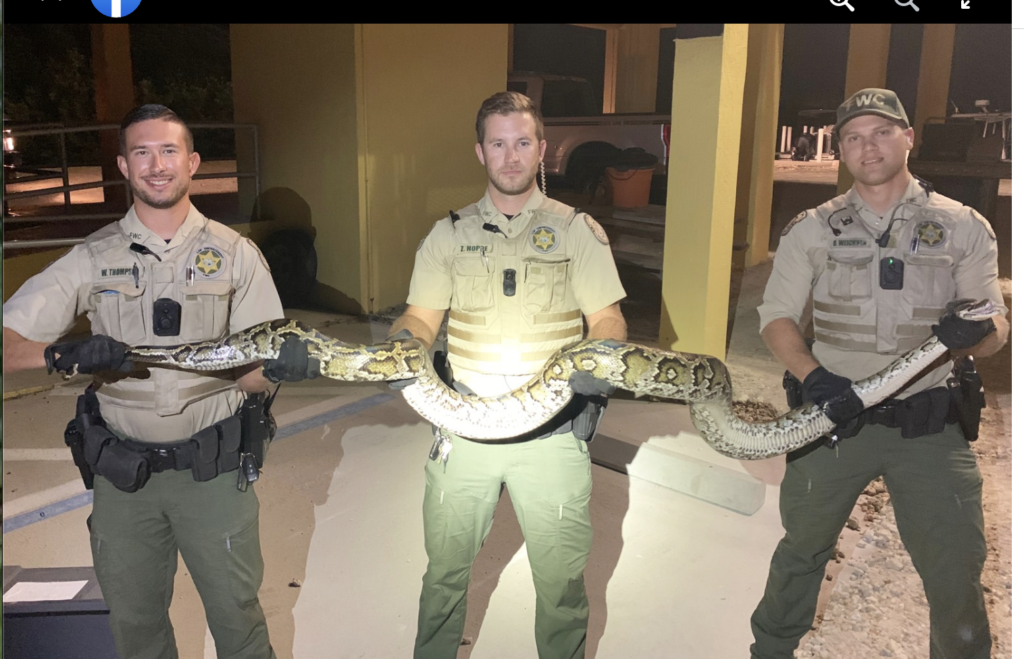

There are the accidents and the crazy drivers and the traffic backups that last for hours because there is but one road to get you from A to B on the entire island chain. There are more than108 mile markers. There is a python every now and again. And it always gets its picture in the Press, held by the smiling captors, who now have something else to jaw about.

There is the wait staff shortage at area restaurants.

And still, there is the book that needs some sort of boost.

There is Key Lime pie from Mrs. Mac’s. Take home a whole frozen pie. Best eaten when warmed by the evening air. There is the sound of water churning on the rocks when the wind is from the west. There is the cartoon voice of the Bronze Frog, sounding like a dog biting a squeeze toy. Bite and release.

There is the slow internet and the sometimes-shaky cell service. There is the morning coffee on the lanai. There is the glass-topped bay when the wind drops. There is the paddle board gliding over the glass, passing over the manatees feasting on sea grass, creating cloudy water for their snouts to break through with a snort.

There are the stars and the moon and the glowworms.

There is the camaraderie and chatter and gossip and crazy talk and earnest talk and hushed talk and vapid talk and talk of where you’re going to eat and what you’re having for dinner and does the grill next to Tamarind work yet, the one closest to the path that leads to the beach that leads to Big Dock where a dozen boats are tied up and await their masters. There are the Rock Harbor rules getting broken regarding maximum dog size, maximum occupancy, minimum length of stay, smoking on the beach, moving chairs on the beach.

Tonight’s diversion is the Oscars telecast. The host doing the interviews must be some influencer or something. I’ve never seen her before, which doesn’t mean much because I usually avoid mass culture. There are very talented people who will be honored tonight, but they all must succumb to the TV telecast culture of worshipping at the altar of CELEBRITY. Is there a person on the planet more excited than a red carpet interviewer? No! They are giddy with their own fame. Queue endless B-roll of movie clips interspersed with behind the scenes clips and howling music. And then the over-the-top intro of tonight’s super host, Jimmy Kimmel. Applause. Inside joke with Nicole Kidman.

But back to this not so good environment for pushing my book. There is a sighting of a sea turtle on the beach but Linda suspects it to be an escaped pet.

How does one think of LinkedIn ad campaigns when there is a baby sea turtle washing up on our beach, when a guy that Linda dubbed the wolfman carries on a 5 hour conversation on the deck behind us, wearing shorts—or is it a bathing suit?— filled with stars. He has hair everywhere. The Wolfman of Rock Harbor.

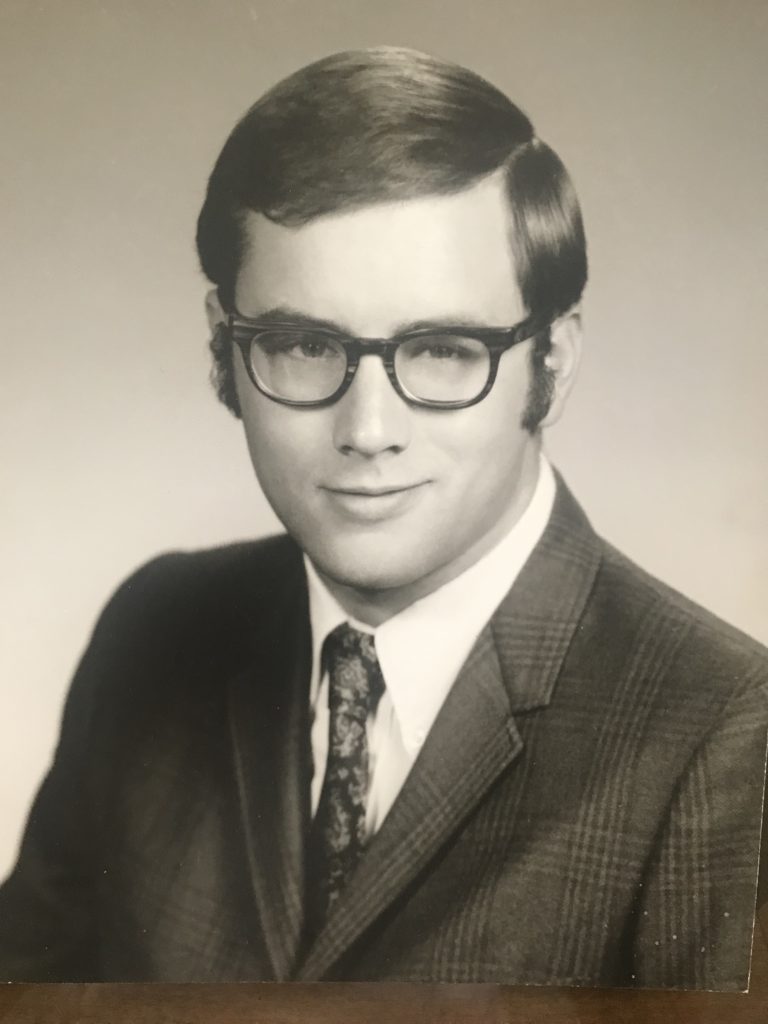

Most here are well done ex-professionals and business owners from up north. The wolfman is different. He has added a touch of something to the predictability of the Rock Harbor society of elderly well-done citizens who have done well. Most here are fine with this life “stage” of resting on laurels, managing bank accounts, showing pics of grandkids on iPhones, napping and in some cases, going to the Caribbean Club to immerse in debauchery. This encourages a coasting vibe. There are few big plans being cooked up at the pool, beyond tonight’s dinner plans. Life is one long vacation until it’s time to depart and head back north. I get itchy after a couple of months and look forward to getting back to my “real” life.

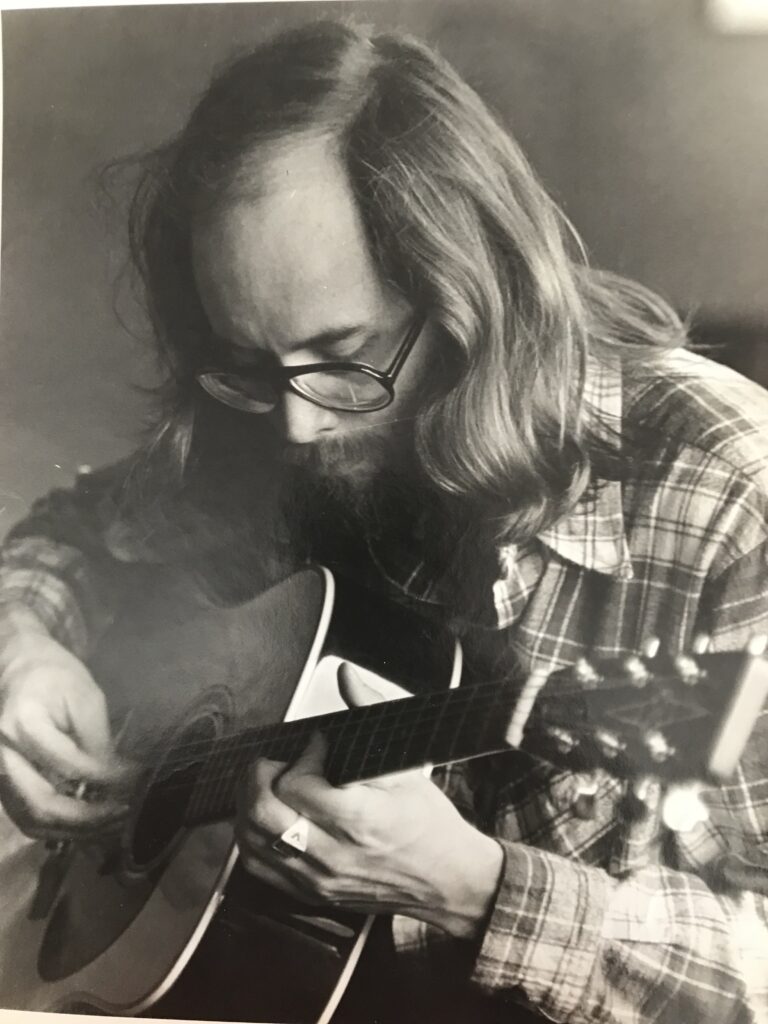

Most view their Rock Harbor life as the reward for a lifetime of accomplishment. I’ve already done it. What more is there to do? Many have worked their asses off. More than a few have been lucky. I doubt anyone here could duplicate my Hardly Working ethos. The feeling that life here is “on hold.” That accomplishment is a rear-view mirror thing. Coming in for a soft landing. (Although with more Miami weekenders buying places, this is changing.) In any cases, we are all escapees.

But we all enjoy sunset. In fact, sunset is perhaps the least political event in Florida. Although there is a conspiracy theory gaining traction that woke culture is trying to assign a neutral gender to the sun. They sun.

A Russian en plein air painter was here in February and we bought her painting of our office tree—the mangrove that we first thought was a buttonwood—whose shade we enjoy during our daily respite from the rest of life, whose branches entice the Nashville Warbler. The tree under which several have read my book. The book that needs my marketing attention, which I find difficult to give.

You know why else it’s hard to work here? And the pool people don’t go to the beach. The Beach people are slightly more apt to notice the Nashville Warbler in the mangrove tree.

-30-