Excerpts from the Hardly Working chapter titled Fried Pie and the Redneck Brothers…

My first Kansas summer found me at a crossroads. By now, it was easier for me to list the things I didn’t believe in than those that I did. I was skeptical of marriage, careers, the Vietnam War, government—in short, most of society’s institutions. That was for squares, man. I wanted no one to tell me what to do or to think. The choices I made had to be mine. All mine. In a notebook I scribbled, live as if your life depended on it.

I hatched a plan, a life map where I would “retire” at the beginning of adulthood. Of course, I would need to work, but as little as possible. And nothing career oriented. Hell, I had no idea what I might do.

Though I never referred to myself as a hippie, that was my stereotype. If you had long hair and wore threadbare clothes, you were a hippie. It was a look. Simple as that. You are how you look. In 1971, if you looked like a hippie, one could extrapolate that you smoked grass, were anti-war and laughed at the American Dream. Being a hippie made you feel like an outsider in a culture that you didn’t wish to fully participate in. And that made you feel kind of good, like it was your best chance to experience the heroic status of the minority. Minority heroes were the hip heroes. Rosa Parks, Caesar Chavez, Huey Newton, the New York rabble rouser, Abbie Hoffman, and Jerry Garcia, the acid guitar shaman with the Latino last name.

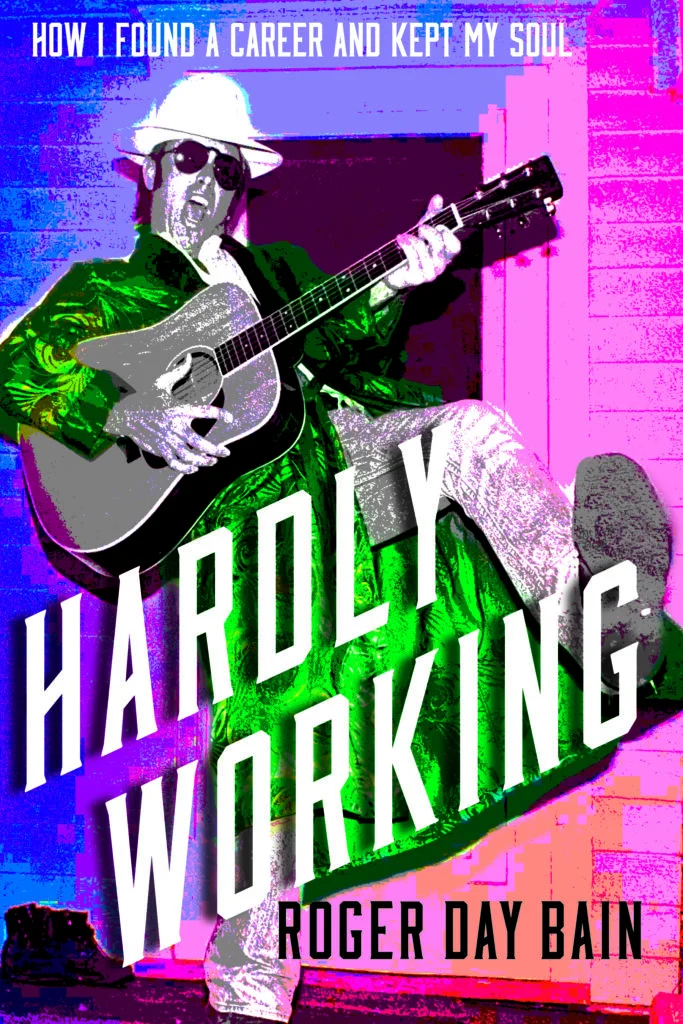

I didn’t believe in society’s institutions, but I did have my beliefs. Very strong ones. I believed in the magic of existence; the magic around every corner; the magic of the moment. And now, the magic of guitar playing. During that melting summer of 1970, alongside teaching myself to seem crazy, I taught myself to play the guitar. I wanted to write songs. My inner voice needed an outlet. Because I hadn’t begun playing during the typical teenage timeframe, I had a lot of ground to make up. A girlfriend bought me a cheap acoustic, I picked up a few songbooks—one by Donovan, I remember—had guitarist friends show me chord changes, and I was hooked. Nothing has had a more profound effect on my life.